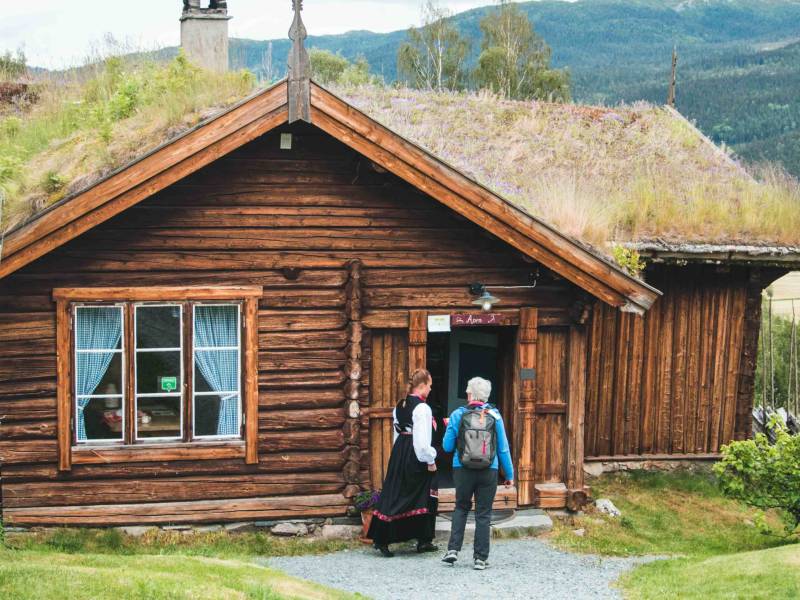

Exploring Nore og Uvdal bygdetun

Provided by:

Nore og Uvdal kommune

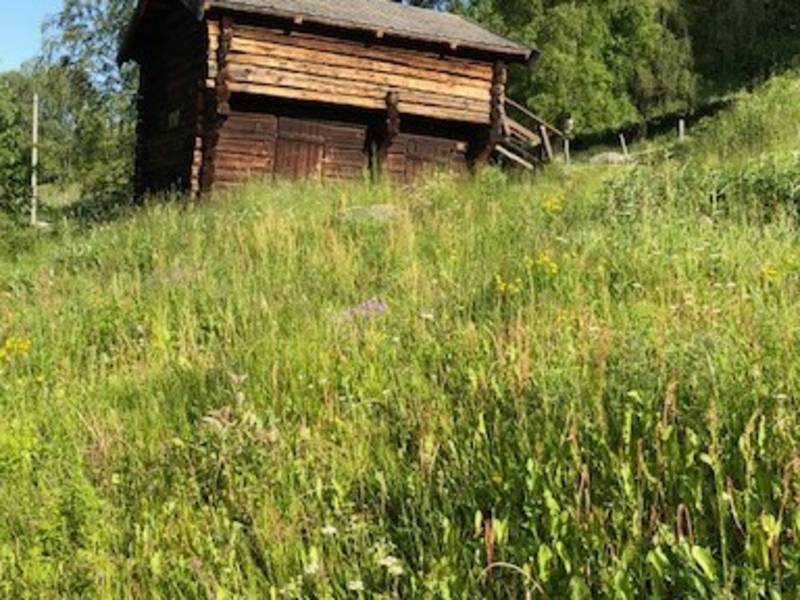

This audio guide is a collaboration between Bygdetunet and the Fortidsminneforeningen. Bygdetunet is located in Kirkebygda with a fantastic view of Uvdal. Nore and Uvdal municipality is located in Numedal one and a half hours drive north of Kongsberg Bygdetunet offers exciting experiences throughout the year. In the summer from June 1 to September 1, you can, among other things, participate in the mowing, enjoy local food, learn about agriculture in the old days and hear the buzz of history in and between the old buildings. In the winter, cultural evenings are arranged with many interesting themes. www.nore-og-uvdal-bygdetun.no/index.html About this audio guide: The narrator's voice is activated automatically as you move within the red circle surrounding each attraction on the map. Press "Download" and you will be taken into the map. Good hiking!